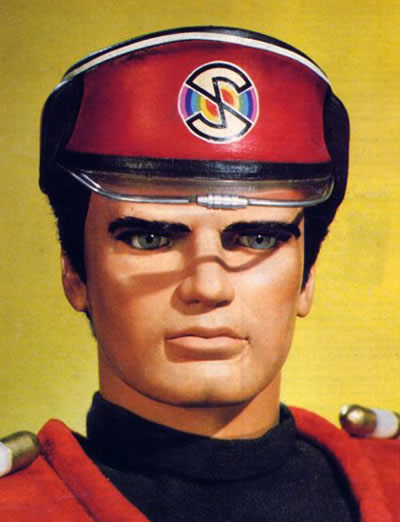

Captain Scarlet

While other television series that came out of Britain in the 1960s have since become cults (‘The Saint’, ‘The Avengers’ and ‘The Prisoner’ come immediately to mind), few have achieved the lasting cult status of the high-tech Supermarionation puppet series produced by Gerry and Sylvia Anderson through Century 21 Studios. ‘Thunderbirds’, ‘Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons’ and ‘Joe 90’ are the best known, although ‘The Secret Service’, ‘Stingray’ and ‘Fireball XL5’ also have their fans. ‘Thunderbirds’ and ‘Captain Scarlet’ were recently repeated (again) on British television, they are still shown all over the world (I’ve personally caught ‘Captain Scarlet’ episodes in Japan, Greece and Argentina), books are still written about them and fan clubs (with regular fan conventions) still take place in Europe and America. A couple of years ago I got a phone call from a stranger. A hopeful voice asked: “Is this the Leo Eaton?” I admitted to being a Leo Eaton but wasn’t sure if I was the Leo Eaton he wanted. “The Leo Eaton who wrote and directed for Captain Scarlet?” he went on. I confessed to being guilty as charged.

While other television series that came out of Britain in the 1960s have since become cults (‘The Saint’, ‘The Avengers’ and ‘The Prisoner’ come immediately to mind), few have achieved the lasting cult status of the high-tech Supermarionation puppet series produced by Gerry and Sylvia Anderson through Century 21 Studios. ‘Thunderbirds’, ‘Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons’ and ‘Joe 90’ are the best known, although ‘The Secret Service’, ‘Stingray’ and ‘Fireball XL5’ also have their fans. ‘Thunderbirds’ and ‘Captain Scarlet’ were recently repeated (again) on British television, they are still shown all over the world (I’ve personally caught ‘Captain Scarlet’ episodes in Japan, Greece and Argentina), books are still written about them and fan clubs (with regular fan conventions) still take place in Europe and America. A couple of years ago I got a phone call from a stranger. A hopeful voice asked: “Is this the Leo Eaton?” I admitted to being a Leo Eaton but wasn’t sure if I was the Leo Eaton he wanted. “The Leo Eaton who wrote and directed for Captain Scarlet?” he went on. I confessed to being guilty as charged.

How little we could have guessed at the time that we were working on shows that would achieve such cult status. Prior to coming to work for Century 21, I’d been an assistant director on television series like ‘Gideon’s Way’, ‘The Baron’ and ‘The Saint’. A friend working for Gerry Anderson at Century 21 asked if I’d like to meet him. Gerry and Sylvia had just completed ‘Thunderbirds’ and were recruiting for a new series about to go into production called ‘Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons’. I was offered the job of First Assistant Director, with the chance of directing future episodes if things worked out. I jumped at it; I was just 22 years old.

Coming out of a live-action TV background where the First Assistant Director runs the set, my job was to bring similar discipline to the puppet shows. Although they’d had assistant directors on the movie ‘Thunderbirds Are Go’ these had been more general assistants to the director. My job was to run the floor (all the activity that surrounds a film set) and keep the director moving fast enough to complete the day’s schedule. This is the primary role of a First Assistant Director, like a Sergeant Major in the Army, keeping set and crew running smoothly while the Director concentrates on the creative job of getting pictures on the screen.

It was a strange transition after ‘The Saint’. None of the puppet crews were used to this type of assistant director and I kept on having to tell the directors “no, don’t worry about that; that’s what I’m here for”. Up through ‘Thunderbirds’, they’d had to do everything themselves. By the beginning of ‘Captain Scarlet’, the operation was becoming more of a factory assembly line and the inclusion of first assistant directors was part of this streamlining operation. As first assistant director on a normal TV series, one of the major roles is keeping the crew quiet during a take. I remember soon after my arrival at Century 21, yelling for quiet and a puppeteer calling down from the rail, “why?” On a set where dialogue is pre-recorded, silence is irrelevant. It was an adjustment, for them and for me.

After the first few episodes, Gerry made good on his promise of making me a director. He first had me directing ‘Thunderbirds’ commercials for Lyons Maid ice-lollies (popsicles here in the US) It was then that I decided that the commercials side of the business wasn’t for me, sitting in a conference room with a bunch of highly-paid advertising executives as they argued endlessly about the precise angle Lady Penelope should hold the ice-lolly. Since I’d also been doing a lot of writing on my own, I wanted to write scripts from the start. Script Editor Tony Barwick agreed that if I gave him a treatment he liked, he’d let me write the script. I’d been thinking for some time about writing a sci-fi short story about someone releasing poison into a big-city reservoir so decided to turn it into a script. “Place of the Angels” was both my first produced script and the first TV show I ever directed.

From that point on, I was one of Gerry’s stable of directors. There was an older, more experienced group, like Desmond Saunders, Brian Burgess and David Lane, all of whom had been with Gerry for some time, and then there were the “young Turks” as we saw ourselves: Ken Turner, Alan Perry, myself and later Peter Anderson. This core group continued with Century 21 through the later Supermarionation series ‘Joe 90’ and ‘The Secret Service’ and into the live-action series ‘UFO’.

At the beginning of ‘Captain Scarlet’, there were still teething problems with the new puppets. The heads were so much smaller then the ‘Thunderbirds’ puppets and the mechanisms kept causing difficulties. The tech wizards had come up with an improved way of getting the puppets to ‘talk’. Theoretically the lip-sync operator, who sat up in his booth that overlooked the puppet stage, just had to play a tape of pre-recorded dialogue. The electronic impulses would then go straight down the metal puppet strings and a solenoid that operated the mouth would respond automatically to the words that were being spoken. Needless to say, it seldom worked so the lip-sync operators ended up just waggling the toggle switch to make the mouths open and shut, just as they’d always done on ‘Thunderbirds’. Then there was painting the strings, the endless amount of time it took puffing with powdered paint to try to make the strings disappear into the background. We had puffers full of every color of powdered paint imaginable but when behind schedule, the puppeteers’ fanaticism about making the strings invisible was always a point of contention.

The studio buildings were on an ugly industrial estate in Slough, about twenty miles out of London, and looked indistinguishable from all the other small factories and businesses in the area. We used to quote poet laureate John Betjeman’s WWII poem, “come friendly bombs and fall on Slough”. One of the buildings did contain bombs since this was where special effects supervisor Derek Meddings operated three special effects crews at all times. Much of the success of ‘Thunderbirds’ and the later puppet series was due to Derek’s special effects; the explosions and model work and his creation of everything from a moon base to the destruction of an Aztec pyramid. He later went on to create the visual effects for many of the Superman and James Bond movies.

Next to the special effects building was the main puppet building, containing two stages with all the associated puppet and wardrobe workshops. There were always two crews operating simultaneously on two different episodes; during any pause in production, there’d be a lot of visiting backwards and forwards between the two stages. All of us on the puppet stages knew that the puppet action was the core of each film while special effects were just there for the bells and whistles. Of course forty years on, it’s the special effects that still cause the most excitement.

Leo Eaton worked on ‘Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons’, ‘Joe 90’ and ‘The Secret Service’ and ‘UFO’. for Gerry Anderson’s Century 21 Productions between 1967 and 1969.

For me, working at Century 21 was like being part of the greatest game in town. I’d wanted to make films since I was 15 (only seven years earlier) and now I had my wish. I was like a kid in a candy store. The atmosphere was so much freer and less structured than in a “real” studio where series like ‘The Saint’ were produced. I’d come from an environment where directors were considered as being next-door to God and stars like Roger Moore, Steve Forrest and Patrick Macnee were treated very carefully indeed, especially by young assistant directors. Now, at 22, I was a director myself (with a produced script to my credit) but it felt more like a bunch of friends getting together to put on a show.

I remember once instigating a water-pistol battle on stage where puppeteers “up on the rail” conducted an all-out attack on the floor crew while I used the director’s booth as a fort to repel all invaders. Eventually the chief puppeteer and the production manager came on set to “discipline the kids” but we’d all had a great time and went back to work damp and happy. By now Gerry Anderson and his senior colleagues probably had no patience for such high-spirits; it was—after all—a serious business, but I’ll bet he used to do just the same in the early puppet days. For me, Century 21 was a glorious sandbox in which to work and play. Of course things got a whole lot more serious when we moved from Slough back to MGM Studios in Elstree to shoot Gerry’s first live-action series ‘UFO’, but that’s another story.